Rediscovering the full range of emotions in Christian music.

By Caroline Williams

Ever since my grandmother taught me to find the middle white note on our baby grand, I’ve been drawn to music, specifically the music of the Church. I’ve accompanied congregations and taught music lessons. But most of all, hymn arranging and improvisation became an unlikely pathway for one young Christian to process depression, anxiety, and her own journey of faith. When almost everything else was confusing, hymns were there with melody and lyrics to speak the truth about God and the world. They stole past the “watchful dragons” as C. S. Lewis would say, sneakily allowing the truth I’d heard in Sunday school my whole life to sink deep and grow roots.

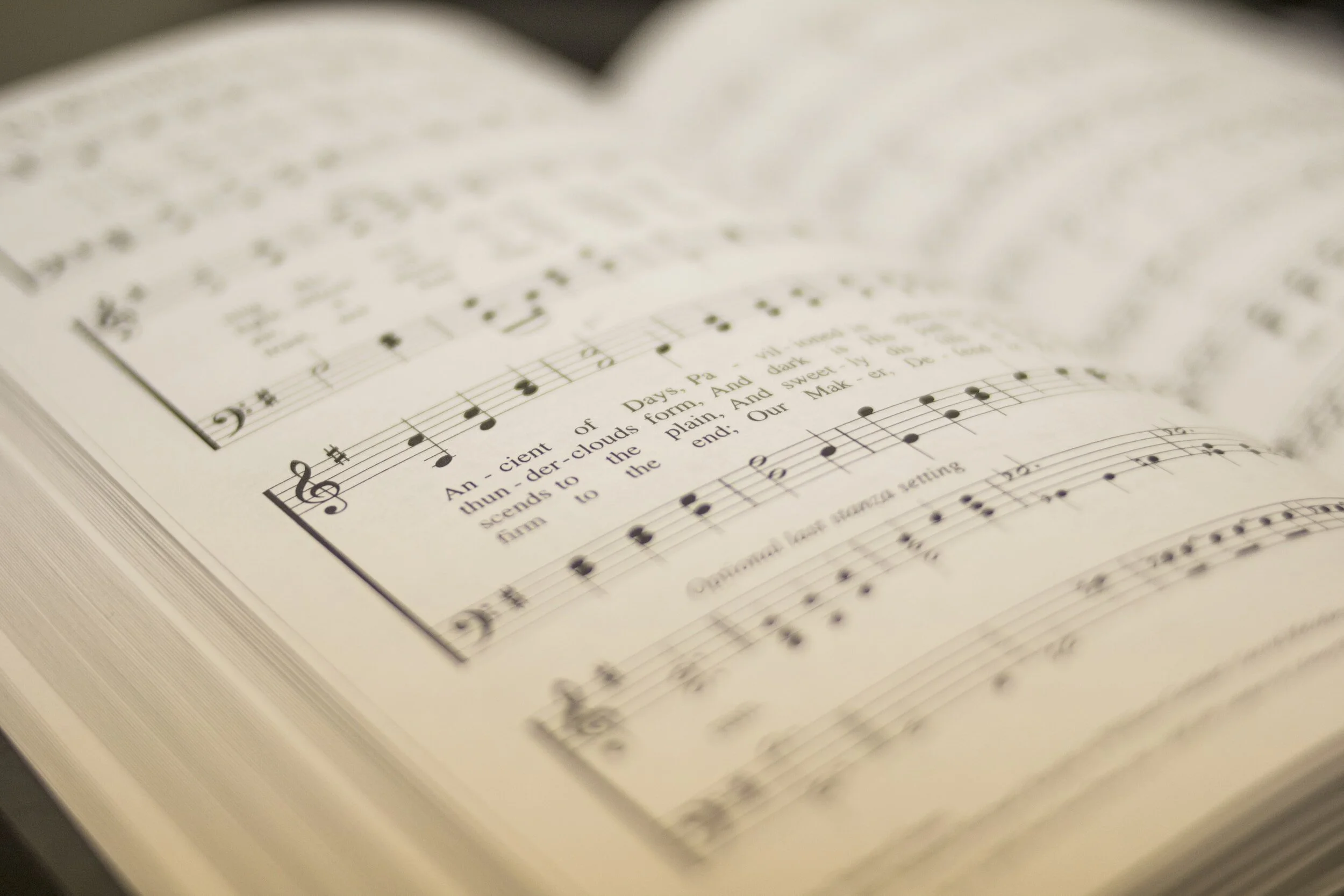

Many of us have heard the story behind the hymn “It Is Well with My Soul.” It’s an account of trust in God despite deep loss. But there are other, lesser-known stories of poets who put pen to paper in times of tragedy. They birthed verses that, married to beautiful melodies, speak the gospel centuries later and became part of our Christian heritage—our true mythos that tells the story of Christ.

One such writer was Karolina “Lina” Sandell-Berg. Not only did she struggle with poor health, but she also witnessed the death of her beloved father by drowning. Her hymn, “Day by Day,” was written out of her grief. Her poetry is poignant, often speaking of God as a father.

The protection of His child and treasure

Is a charge that on Himself He laid;

“As thy days, thy strength shall be in measure,”

This the pledge to me He made.

George Matheson suffered heartbreak when his fiancée learned that he would soon go blind and abandoned him. He penned the stunning verses to “O Love That Will Not Let Me Go” and later wrote,

Something happened to me, which was known only to myself, and which caused me the most severe mental suffering. The hymn was the fruit of that suffering. It was the quickest bit of work I ever did in my life.

It is said that he wrote the hymn on his sister’s wedding day. Perhaps the mental suffering he referred to was the ache of being abandoned by someone he thought loved him. Yet the comfort he found in a love that would never let him go lives on through his words.

O Joy that seekest me through pain,

I cannot close my heart to thee.

I trace the rainbow through the rain,

and feel the promise is not vain,

that morn shall tearless be.

Their words are far from mere relics printed in hymnbooks but intimate art—an up-close view of beauty from ashes. The lyrics connect my story to their story, and both of our journeys to the Great Story.

Wallace Stevens commented that “the poet is the priest of the invisible.” Poetry in the psalms and hymns exposes the hidden parts of our stories as we engage with them, allowing us to spy common ground and courage we might not have otherwise.

“Great Is Thy Faithfulness”

A few years ago, I was processing personal pain and arranged a new take on the hymn “Great Is Thy Faithfulness.” It began gently, with melodic chords. But it quickly changed into a harsh minor key, the entire second verse infused with Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. The notes held my aching, broken lament, the space between my soul and the truth I still believed about God. The music I played was furious but the lyrics told a paradoxical story of hope. Sometimes, I’d pull my hands from the keyboard and let the dissonance linger in the air, unable to convince myself that there was any point in playing the next buoyant chords. But I couldn’t leave it there, so the key changed into triumphant C major and ended on a mountaintop of octaves and bold chords. Joyful. Full circle. Complete.

I’ll never forget my pastor at the time listening to the arrangement and commenting with a gentle twinkle in his eye, “I have a feeling there’s quite a story behind that arrangement. I’d love to hear it sometime.” He knew.

That arrangement of “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” is one of my personal Ebenezers of the “hither by thy help I’ve come” variety. Each time I play it and muscle memory takes over, I am reminded of the prayers God answered. Who knew something as simple as a tune could carry such eternal weight?

“Acknowledging pain in this world and sharing hope that resonates.”

Andrew Peterson says in his book Adorning the Dark that “By God’s grace, a good song can inject beauty into some unsuspecting passerby and lead them to the truth.” Not only that, but by inheriting melodies from past generations, we can find solace in molding fresh, healing beauty upon that foundation.

What if embracing goodness and community doesn’t have to look like a pasted-on smile, a precise performance, or a social-media-worthy snapshot? What if, like King David’s psalms, it sounds honest in both celebration and lament? What if, just by singing and writing and composing and collaborating and listening, we’re creating cosmos—order—out of chaos?

Hymns, new and old, are part of what allows Christians to truly acknowledge pain in this world and share hope that resonates—helping us trace the rainbow through the rain. In creating good, brave art, and in embellishing/re-imagining old themes, we’re linking arms with poets like Lina Sandell-Berg, George Matheson, and the psalmists. Their words still ring out during church services, in tearful prayer at a keyboard, as a lullaby to sleepy babies, or around a fireside circle of friends with a lone guitar. The song of Aslan in Narnia is still reverberating through the centuries.

_________

Caroline J. Williams is a copywriter and editor by day and a writer by night. She authors the Cosmos and a Cuppa publication for readers who feel the tension of darkness and light in life and are curious about noticing “the weight of glory” in our world. She lives in south Mississippi with her husband and two sons. When she's not embarking on adventures with her people, she can be found sipping a dirty chai while trying to conquer a stack of books. Connect with her here.