Paintings, sculptures, and murals once pointed to godliness, says scholar John Skillen. Could it — should it — happen again?

By John Skillen

For a millennium and more of Western Christianized culture, character assessment and moral perception were seen through the lenses of the Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. A foursome of virtues included Prudence, Temperance, Justice, and Fortitude. A threesome—Faith, Hope, and Love—reflected a famous passage by St. Paul in 1 Corinthians, chapter 13. Four vices were Foolishness (in contrast with Prudence); Wrath (opposed to Temperance); Injustice (versus Justice); and Inconstancy (opposite Fortitude). The last vices were Infidelity, Desperation, and Envy (opposite Faith, Hope, and Love).

Descriptions of the virtues and vices were abundant: in treatises, sermons, poetry, and popular theater. In Dante’s Commedia and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales the virtues are not just a motif appearing now and again, but serve as the very scaffolding of the narrative.

More surprising for most of us moderns, the virtues and vices made their appearance in every aspect of the built environment, indoors and out, fittingly chosen for the purpose of the setting—and appearing in just about every artistic medium.

In 2016, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts hosted a remarkable exhibit of dozens of works by the Della Robbia family during the Italian Renaissance. Luca della Robbia had perfected the recipe for the shiny, colorful, glazed terracotta that became the trademark medium of several generations of the Della Robbia family. Featured in the exhibit was a circular rondel (almost 5 feet in diameter), the work of Luca's cousin Andrea della Robbia from around 1475. It incorporated the striking terracotta.

Della Robbia exhibition, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2016 (photo from the author)

The comments I overheard during my visit to MFA Boston were appreciative but they concerned the technique and beauty of the work, not its subject. In the rondel, a leafy wreath of fruit frames the figure of a young woman holding a mirror in her right hand while grasping a snake in her left hand. The back of her head is in fact the face of a mature man. A lock of the young woman’s hair merges into the man’s long beard.

This visualization of Prudence in Andrea della Robbia’s terracotta sculpture may be enigmatic, even disconcerting, to us today. But it was readily decipherable for centuries. What are we to make of it?

Two-Faced Lady Prudence (The Met’s Open Access policy allows use of its photographs in the public domain.)

Two-faced Lady Prudence is equipped for deliberation and astute decision-making. With her mirror, she knows herself; she also can look ahead and behind. With the backward-looking visage of a wise and experienced old man, Prudence can learn from the past, drawing on the experience of tradition. And the snake? Likely in reference to Jesus’s injunction in Matthew’s gospel: “Therefore be wise as serpents and harmless as doves” (10:16).

Prudence is the virtue by which, learning from past experience and extrapolating likely futures, we can make wise decisions in present circumstances. A medieval proverb puts it succinctly: Ex praeterito—praesens prudenter agit—in futura actione deturbet (“from past experience the present acts prudently less future action be vitiated”).

In the book accompanying the Boston exhibition, the directors expressed optimism about the effect on visitors of these “enduring works with profound artistic and spiritual meaning”:

In their own time, these works played roles in civic, religious, and domestic spheres, expressing ideas, aspirations, and sentiments of their patrons, owners, and viewers. . . . In our time, the joyous surfaces, with their bright color and vivid contours, seem remarkably contemporary, speaking with a freshness that brings the act of devotion alive. These works’ color and surface . . . have allowed—even encouraged—the celebratory, festive side of devotion in a manner that has enlivened spiritual reflection.1

Alas, I’m not convinced that “joyous surfaces, bright color and vivid contours” are sufficient to prompt an “act of devotion” when the virtue of prudence has little currency in the thought, language, desires, and emotions of most people nowadays.

The virtue of Prudence is pretty much erased from the ordinary discourse of contemporary society. Even the word “virtue” is inactive in quotidian social conversation. All the more unlikely would a contemporary artwork treating Prudence be displayed in a public place. We could say that Prudence—and perhaps her six sister virtues as well—has little if any societal presence in our contemporary visual landscape.

Below I shall provide a glimpse of the variety of settings in which the virtues and vices were depicted visually in medieval and Renaissance towns: in town halls and meeting rooms, monasteries, doors, bell towers; including public fountains, libraries, and private palazzi, and in every area of churches. Some would be seen only by families or the enclosed communities in monasteries or closed-door committees.

Many were in the reach of every sector of the populace, though. Visualized virtues and vices surely played a significant role in forming the understanding and discourse of an entire community.

Did these shared lenses of good and bad character actually shape the character of individuals and town citizenry? And if so, can the visual arts again take up something of their premodern role in teaching, remembering, and inspiring the virtues?

My historian-friend Thomas Albert Howard gives an optimistic word in his fine essay on Prudence: “I am persuaded that such visual encounters with the virtues help students think about appropriating them in their own lives.”2

Virtuous Art

The following brief gallery of paintings and sculptures from 14th- to 16th-century Italy illustrate how teaching good and bad character through beautiful visual art was pervasive.

Scrovegni Family Chapel, Padua

Scrovengi Family Chapel (photo from the author)

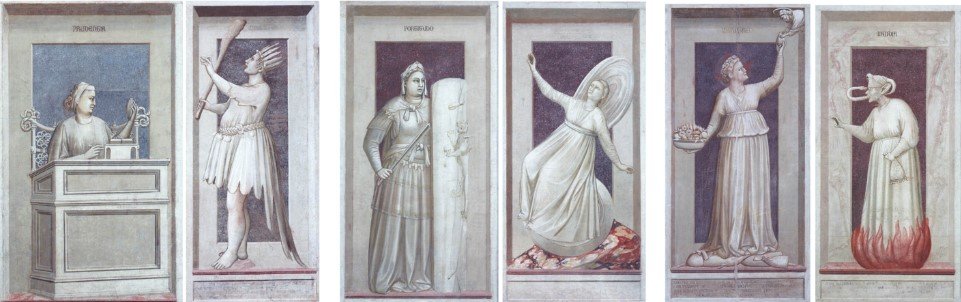

In the first decade of the 1300s, the already-renowned painter Giotto was commissioned by the wealthy Scrovegni family in Padua to fresco the walls of the family chapel with a series of episodes from the lives of Mary and Jesus, spiraling around the walls of the chapel, from top to bottom.

Below the narrative scenes are personified-depictions of virtues and vices, at eye-level. The vices are: Foolishness, opposite Prudence; Inconstancy opposite Fortitude; Wrath opposite Temperance; Injustice to Justice; Infidelity to Faith; Envy to Love; Desperation to Hope. In the borders of the painted niches, painted labels identify the virtue or vice. Below are three pairs:

Prudence (Prudentia) Foolishness (Stultitia) Fortitude (Fortitudo) Inconstancy (Inconstantia) Love (Karitas) Envy (Invidia)

The pairs, however, are not placed adjacent to each other, but rather face each other on opposite sides of the chapel. The arrangement creates a sense for the worshippers—the family and guests invited to attend mass in the chapel—as being framed, or sandwiched, in a sort of decision-space for identifying and assessing one’s character.

The Sala dei Nove in the Town Hall of Siena

The Sala dei Nove (photo from the author)

At the heart of the Palazzo Pubblico of Siena is the committee room where nine “good and lawful merchants” served two-month terms as a sort of central executive committee, distilled from the large council of three hundred that met in the adjacent great hall. Every square inch of the Hall of Nine is frescoed (by local artist Ambrogio Lorenzetti) with the contrasting landscapes and town-scapes of a city well or badly governed, highlighted by figures representing the virtues and vices of “good and bad government,” all with painted labels.

The largest figure on the wall of good governance represents the commune of Siena. Winged figures over this male’s head represent the three scriptural virtues of Faith, Hope, and Love, with Caritas in highest position. Seated by threes on either side of the main figure are female representations of the four cardinal virtues along with the additional two of Peace and Magnanimity (generosity for the public good). The second-largest figure commands the left side of the wall, representing Justice, with the winged figure of Wisdom over her head. From balanced scales of distributive and commutative justice come two ropes twisted together in the hand of the personage of Concord; she in turn entrusts the rope into the hands of 24 leading citizens who attach it to the rod of governance.

The Belltower in Florence

The Belltower in Florence (photo from the author)

Immediately adjacent to the stupendous cathedral in Florence is the great Bell Tower, built in the mid-1300s under the design and supervision of three master builders, including Giotto. Decorating all four sides of the Campanile is an encyclopedic series of framed reliefs honoring every aspect of Florentine society, governance, education, worthy labors, and its religious and moral underpinnings. A program of hexagonal panels includes a wide array of vocational “arts,” including navigation, agriculture, building, architecture, hunting, wool-working (a major element of Florence’s economy), medicine, painting, music, poetry, even the “art” of festivals. Lozenge-shaped panels in groups of sevens depict the sacraments, liberal arts, planets—and the Seven Virtues.

Florentines, from every level of society, would have reason to pass under the bell tower daily. One can imagine the families, and the youngsters, looking up and seeing Mom’s work of weaving Florence’s prized fabrics and Dad’s work as a stone mason. The godly pastimes and the festive holy-days of the church year are figured, along with the youngsters’ own learning of the “liberal arts” in school, and the three-plus-four virtues that make for a life well lived.

The Baptistry in Florence

The Baptistry in Florence (photo from the author)

Steps away from the Campanile is the octagonal-shaped Baptistry, with three sets of magnificent bronze-cast doors with series of panels depicting scenes from the Bible. The earliest-made doors, the work of Andrea Pisano in the 1300s, presented key episodes from the life of John the Baptist, fittingly for a baptistry. The eight panels at the bottom of the doors—two layers with four scenes each—depict figures of the four cardinal virtues on the lower row, and the three theological virtues in the upper row.

What virtue was chosen to complete faith, hope, and love? Humility, the virtue of the Baptizer who declares, “He who comes after me ranks ahead of me because he was before me, . . . the thong of whose sandal I am not worthy to untie” (John 1:15, 27 RSV).

The Chapter House of the Monastery of Santa Maria Novella, Florence

The Chapter House (photo from Gianna Scavo

In the late 1360s, the Dominican friars of Santa Maria Novella monastery in Florence commissioned the respected Florentine painter Andrea Bonaiuto to fresco all four walls and the ceiling of the meeting room of the community—the “chapter house,” found in every monastery. Taken together, the assigned scenes present every aspect of the order’s mission of preaching and teaching. An entire wall is given to the educational program of the scholarly “order of Preachers.”

Seven figures on one side represent the foundational liberal arts of grammar, logic, rhetoric, and the quadrivium subjects of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. Seated below each “art” is an historical exemplar. On the other side are representations of the advanced studies essential for what we might call a rigorous seminary training. Presiding over this gathering, is the order’s greatest philosopher-theologian, St. Thomas Aquinas. Seated beside St. Thomas are ten exemplars from Old and New Testaments, including Job, Moses, David, Solomon, Isaiah; the gospel writers and the apostle Paul. In the sky above and around the “angelic doctor’s” cathedra is a set of angels, four below and three above: the Seven Virtues, with Charity at the pinnacle. These mark the concerns and character of St. Thomas, and the foundation and goal of sound learning.

The Seven Virtues in the Merchant’s Court in Florence

The Seven Virtues (photo from Judy Gaede)

This beautiful set of the Seven Virtues was commissioned (in 1469) as the decoration surrounding the court in Florence that adjudicated disputes and cases of malpractice among the seven guilds engaged in commercial activities. The implication is that to guide and fulfill the work of Justice, the judges must draw on other virtues such as prudence, temperance, love, and so forth. The paintings are now displayed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. I have never heard any natural conversation among the visitors about the subject matter; the prevalent topic is the stylistic differences between the two artists involved.

Prudence, Justice, Temperance, Fortitude, Faith, Hope, Love

—-

Dr. John Skillen taught medieval and Renaissance literature at Gordon College for several decades, then developed an arts and history program in Orvieto (Italy), where he and his family lived for a number of years. He is the author of Putting Art Back in its Place and Making School Beautiful.

--------------

1 Della Robbia: Sculpting with Color in Renaissance Florence, editor and chief writer Marietta Cambareri, with contributions by Abigail Hykin and Curtney Leigh Harris (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Publications, 2016), 7.

2 Thomas Albert Howard, “Seeing with All Three Eyes: The Virtue of Prudence and Undergraduate Education,” in At This Time and In This Place: Vocation and Higher Education (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 217, footnote 3.