How the Last Robot on Earth Gets Love Right

By Timothy Lawrence

To worship rightly is to love each other.

– John Greenleaf Whittier

Introduction

During the 15-year period that many refer to as its “Golden Age,” spanning 10 feature films, Pixar Animation Studios was regularly lauded for its groundbreaking computer animation and whip-smart screenwriting. The real secret to Pixar’s success, though, was the maturity of the films’ thematic interests. In defiance of the popular belief that “cartoons” should shy away from serious thought – all the better for easy consumption by their adolescent target audience – Pixar’s greatest films actively pressed into profound existential questions. Taking as a starting point some object or creature with a clearly defined purpose – a toy, say, or a monster – Pixar constantly returned to questions of telos: “Why am I here? What am I meant for?”

In 2008, at the peak of its creative powers, Pixar presented its richest and most sweeping answer to those questions in the form of Wall•E, its ninth feature film. One might even say that Wall•E represents a downright theological answer to Pixar’s perennial existential questions. The film makes no direct, explicit reference to the Christian faith of its director, Andrew Stanton, but like J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, it overflows with veiled allusions to the goodness of the God it never mentions by name. Over the course of its 90-minute runtime, Wall•E sets forth a profoundly Christian vision of the entire cosmos. It envisions the Creation as a place designed for fruitful labor and grateful contemplation, harmoniously animated and sustained by the Love that moves the sun and the other stars.

Why are we here? What are we meant for? We are here to work, and we are meant for Love.

1

Man goes to his work

And to his labor until the evening.

– Psalm 104:24

Wall•E opens with stunning shots of outer space, pictures of celestial beauty, set to a song from Hello, Dolly! – “Put on your Sunday clothes, there’s lots of world out there!” The film’s editing is matched to the rhythm of the music, creating a magical effect: the images of the natural world and the man-made music, synchronized in perfect harmony, declare the glory of God together. After this brief salvo of sublimity and beauty, though, the camera turns its gaze away from the glory of the sun – the fiery source of life-giving light – and descends to the dingy surface of the disheveled planet Earth. The music fades from the soundtrack; the light and color of the cosmos give way to the smoggy clutter of a ruined world.

And yet: the music persists, in a diminished form, as the tinny recording that Wall•E plays while he trundles through the wasteland. “Put on your Sunday clothes, there’s lots of world out there!” He finds the cover of a metal trash can among the detritus; its reflective surface glints, catching the sunlight; and its round shape, too, reflects the sun. It sparks something in Wall•E; he keeps it.

The beginning of Wall•E evokes the Book of Genesis, which is the beginning of the Christian story. The heavens declare the glory of God: “God saw everything that He had made, and indeed it was very good.”[1] However, the Earth is marred, cursed to fruitlessness, by the sin of fallen mankind: “Cursed is the ground for your sake; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life.”[2] Nonetheless: “Put on your Sunday clothes, there’s lots of world out there!” The original glory of the Creation still shines through the haze; the music of the spheres still echoes on Earth; and even the imperfect things made by man’s imperfect hands can reflect the perfect Maker.

The figure of Wall•E evokes the first man, Adam. The name “Adam” etymologically links man to the earth (Hebrew adamah) out of which God made him, and over which he is meant to have dominion. In the same way, Wall•E is linked to the Earth by his name: “WALL•E” stands for “Waste Allocation Load Lifter, Earth-Class.” His rusty, dirty, cube-shaped metal body is of a piece with the garbage that his maker has charged him to cultivate and order. Like Adam naming the animals in Eden, Wall•E takes pieces of trash to his home and categorizes them, placing like with like. Wall•E has an animal for a companion, in the form of his faithful cockroach friend, but like Adam, he lacks “a helper comparable to him.”[3]

As the film begins, Wall•E is roaming to and fro on the Earth, crushing the garbage into cubes and stacking the cubes into ziggurat-like towers of Babel that stretch toward polluted heavens. “What profit has a man from all his labor / In which he toils under the sun?”[4] Is this not the fruitless toil of Adam’s curse, a dystopian vision of endless, meaningless work that can never fulfill the worker? That is not how Stanton’s film plays it, though. Clearly, Wall•E’s situation is far from ideal – it is the result of a catastrophic human failure – but he is apparently untroubled by any ambiguity about the long-term purpose of his labor. As Solomon writes, “Nothing is better for a man than that… his soul should enjoy good in his labor. This also, I saw, was from the hand of God.”[5] Wall•E seems largely content to continue on in “blind and humble obedience to [his] vocation,”[6] tending the trash indefinitely, cubing most of it and preserving those items that spark curiosity, delight, and wonder.

Wall•E finds contentment in his labor because of his proper, healthy posture towards the world he lives in. Though the material he works with seems unlovely, Wall•E spends his days humbly attending to it and finding unexpected beauty in it. Like a gardener – Adam’s original vocation – Wall•E works with his hands. He gathers the trash in as if it is soil and uses his body to shape it into an orderly, beautiful form. His labor is thoroughly embodied, incarnational, earthy.

Wall•E’s attunement to the world around him extends beyond his labor to the larger rhythm of work and rest that characterizes his life. Wall•E is a machine in a natural world that seems hopelessly obscured by manmade rubbish, a world “bleared and smeared with toil.”[7] However, as a solar-powered robot, Wall•E needs sunlight to function, and so the greater part of his life is shaped by the natural cycles of the heavens. As such, his existence has a sort of sane simplicity to it. When it is day, he works; when it is night, he rests. The sun does not only charge Wall•E with literal life; because his life is ordered around its rising and setting, the sun also sustains him with a life-giving sense of structure and routine.

When he comes home to rest after each day’s work, Wall•E takes off his treads, the way a man might remove his shoes upon entering his house. Just as he conforms himself to the patterns of the sun, Wall•E models himself after the humans who made him, and so his rest becomes more than just a utilitarian concession to necessity. His rest does not merely serve to recharge him for the next day’s work. Rather, his rest – ceremonially set apart (which is to say, made “sacred”) from his work by the removal of his treads – makes him more human. Machines do not rest in the true sense – they cannot be said to enjoy leisure – but humans do. Wall•E rests in ritual imitation of those who made him; humans rest in ritual imitation of the God who made them, then rested on the seventh day and commanded that they do likewise. Josef Pieper writes, “[W]e may read in the first chapter of Genesis that God ‘ended his work which he had made’ and ‘behold, it was very good.’ In leisure, man too celebrates the end of his work by allowing his inner eye to dwell for a while upon the reality of the Creation. He looks and he affirms: it is good.”[8] God does not rest because He needs to fend off exhaustion; He rests to celebrate His work and affirm its goodness. Humanity is called to do the same: “Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh is the Sabbath of the Lord your God… For in six days the Lord made the heavens and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested the seventh day.”[9] Or, in Josef Pieper’s words: “[I]n divine worship a certain definite space of time is set aside from working hours and days, a limited time, specially marked off – and like the space allotted to the temple, is not used, is withdrawn from all merely utilitarian ends. Every seventh day is such a period of time. It is the ‘festival time’, and it arises in this way and no other.”[10] To put it another way: “Put on your Sunday clothes, there’s lots of world out there!”

Each night, Wall•E pores over Hello, Dolly! as if it is a sacred text, and in a way, it is. Hello, Dolly! gives him a vision of the good life; he aspires to emulate the happiness of the musical’s human characters by going through the movements of their dance, using his round trash can cover as a makeshift hat.

It is through Hello, Dolly! that Love enters Wall•E’s workaday world. “It only took a moment to be loved a whole life long,” sing the characters onscreen as they hold hands, and Wall•E, enraptured, contemplates this moment of Love deeply. He presses “Record,” taking the music into himself; the lovers’ hands are reflected in his eyes; he haltingly interlinks his own two hands in imitation of what he sees. Up to this point, Wall•E’s hands have been defined as the instruments of work; now, it is suggested that hands could become the instruments of Love. Wall•E has used his hands well to commune with the Earth; now, he longs to use his hands to commune with a Beloved who is not of this Earth. Outside, he looks heavenward and plays back the recording: “It only took a moment to be loved a whole life long.” Reflected in Wall•E’s eyes, the stars become – as they are in Dante – shining witnesses of the Love that moves them.

2

In that book which is my memory,

On the first page of the chapter that is the day when I first met you,

Appear the words, “Here begins a new life.”

– Dante Alighieri, “La Vita Nuova”

It is with fire – the Dantean symbol of divine Love, the stuff of which the stars are made – that EVE comes down into Wall•E’s world. In Wall•E, as in Dante, Love is not a tidy, sentimental, pleasant emotion but a fiery, disruptive, even destructive force – and Wall•E, like Dante, is both smitten and rightly terrified by this heavenly intrusion into his world. It is no coincidence that “smitten” is derived from the verb “to smite”; in the eyes of the Lover, the Beloved always appears celestial, and the things of earth always tremble before the things of heaven. Of Dante’s first sight of Beatrice, Charles Williams writes, “A kind of dreadful perfection has appeared in the streets of Florence; something like the glory of God is walking down the street towards him… a wonder was on earth which shone as if in heaven.”[11]

Ultimately, Beatrice’s role in Dante’s Comedy is to help the poet see the beatific vision – the fiery celestial rose where God dwells in unapproachable light at the culmination of the Paradiso. Protestants are prone to object that the Catholic Dante’s veneration of Beatrice is idolatrous, but Dante is always clear that Beatrice herself is not the beatific vision; rather, her loveliness is only one glimpse of God’s loveliness, from which it is derived. Beatrice is not an idol but an icon, pointing beyond herself, arresting Dante’s gaze in order that Dante might see God through her. This theme of transformed vision is poetically expressed in the motif of Beatrice’s eyes. When the love-struck Dante gazes into Beatrice’s eyes, he sees the heavenly spheres reflected in them; by contemplating her, he learns to contemplate the cosmos as she does. The motif appears in Wall•E with one key adjustment: Wall•E, not his beloved EVE, is the one with reflective eyes. As the love-struck Wall•E follows EVE around, generally making a fool of himself as lovers are wont to do, the film evokes the Beatrician dynamic and the Dantean image of the heavenly rose through Louis Armstrong’s “La Vie En Rose” (that is, “Life seen through rose-colored glasses”): “When you speak, angels sing from above / Everyday words seem to turn into love songs.” EVE’s presence fundamentally reorders Wall•E’s vision of the world; suddenly, he sees everything around him charged with new and lovely significance.

Beatrice calls Dante to a new life – a life oriented towards the Other, which is to say, a life of Love. The shock of first love “frees [Dante] from consideration of himself”; the sight of Beatrice “filled him with the fire of charity and clothed him with humility.”[12] EVE sparks “new life” of a kind in Wall•E, and she is also oriented towards new life more broadly in the form of the plant she has been sent to Earth to search for. The fiery, heavenly, spiritual “new life” EVE represents to Wall•E is closely linked with the fruitful, earthy, physical “new life” of the plant. The plant and the sun are visually linked by a transition that slowly fades from one to the other, overlaying EVE’s round plant icon with the bright circle of the sun:

Just as Wall•E was symbolically linked to the trash he worked with, it is no coincidence that Wall•E and the plant both derive their life from the sun. The new life of the plant is the fruition of Wall•E’s work – work that, it turns out, always had a horizon he was not fully cognizant of. The telos of his labor has never merely been to order the Earth as he likes, but to restore it to a state that humanity might return to, and EVE’s role, as an Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator, is to judge whether that labor has been fruitful or not. She reveals that Wall•E’s work has always been ultimately oriented towards Love – not just of the Creation, but of his creators.

EVE, then, opens Wall•E’s eyes to the true nature of his work, and this is highly Dantean. According to Williams, “[Beatrice] is, in the whole Paradiso, [Dante’s] way of knowing, and the maxim is always ‘look; look well’.”[13] Beatrice calls Dante, first, to attend to herself: to “look well” at the beauty of one woman. But the vision of the Beloved is only ever the first step on the Way, and Dante is always called to attend to what is beyond Beatrice: to “look well” at the City, at the Cosmos, and finally at God. The Beloved opens the eyes of the Lover not that he might fixate on her with a kind of idolatrous tunnel vision, but that he might look on all the Creation with Love, and thus see it as it really is. True romance is not an illusion but an unveiling of a spiritual reality. The refrain of Beatrice is “riguarda qual son io” – “see me as I am.”[14]

This Dantean understanding of Love is beautifully expressed in the scene where EVE comes to Wall•E’s small, tidy, neatly ordered home and begins obliviously wrecking the place through the sheer superabundance of her vitality. When a man falls in love, it is as if Love enters the house of his soul and turns the place upside down, moving the furniture around as it sees fit. C.S. Lewis describes the phenomenon nicely in The Four Loves: “Eros enters [the Lover] like an invader, taking over and reorganizing, one by one, the institutions of a conquered country.”[15] Love always disrupts, but it is, taken rightly, a constructive disruption. EVE shows Wall•E, for the first time, the true purpose of all the items he has collected over the years. They have been neatly ordered, but not truly understood. Wall•E needs EVE to show him that a lightbulb is meant to shine, a Rubik’s Cube is meant to be solved, and a lighter is meant to produce fire. As EVE illuminates Wall•E’s home with the fire of Love, the song from Hello, Dolly! plays again: “And that is all that love’s about…” Wall•E looks from the fire of Love to EVE’s face, lit by the warmth of that fire, and then, trembling, reaches for her hand…

But Wall•E is only starting out on the path of Love. EVE rebuffs his hand; attempting to impress her, he shows her the plant; and the revelation of the plant sends EVE back to the heavens, and Wall•E with her. The lyrics of “Put On Your Sunday Clothes” proclaim, “We won’t come home until we’ve kissed a girl!” – and this is true of Wall•E in a profounder way than the song immediately indicates. Wall•E’s idea of home has been completely redefined by EVE. Now, home is where EVE is; there is no home without her. When EVE leaves the Earth, Wall•E must go with her and leave behind all he has ever known. He must leave his home if he is to come to his true home.

Like Beatrice with Dante, EVE sparks Wall•E’s ascent. She fills him with the fire of Love, and the nature of fire is always to ascend to the heavens from which it came. When he ascends with EVE, Wall•E comes closer than ever to the fire of Love, the sun from which his life is derived. As her spaceship flies near the Sun, Wall•E opens his solar panels and is instantaneously charged to complete fullness. We might recall that line from Hello, Dolly! – “It only took a moment to be loved a whole life long.”

3

Neither plenitude nor vacancy. Only a flicker

Over the strained time-ridden faces

Distracted from distraction by distraction

Filled with fancies and empty of meaning…

– T.S. Eliot, “Burnt Norton”

Beatrice inspired Dante to set out on an epic quest to unite with his Maker; EVE sets Wall•E on an epic quest to unite with his makers, but Wall•E’s theological dimension becomes complicated here, because Wall•E’s human creators are far from perfect reflections of their Creator. In fact, Wall•E’s role in the story is not to be redeemed by his creators but to redeem them.

At first glance, the gleaming, pristine Axiom – the starship carrying all of humankind in the dark depths of space – might seem preferable to the dirty, soiled Earth. However, of the two worlds, the Axiom is the disordered one. Work, the Creation, and man’s creations – all the elements that were harmoniously bound together by Love on Earth – have been cleanly, fatally isolated from each other on the Axiom. The lives of the humans and robots on the Axiom are characterized, above all else, by profound disconnection – from the world around them and from each other.

In contrast to the real sun that shaped Wall•E’s life on Earth with its unalterable natural patterns, the false sun on the Axiom is dictated by the humans’ whims. When Wall•E oversleeps, he has to blunder groggily outside to absorb the sun’s life-giving light again, but when the Axiom’s Captain oversleeps, there are no real consequences: he simply sets the clock back, sending the digital sun backwards across the digital sky so he can give his morning announcements. Humans living in a world so profoundly disconnected from reality cannot help but grow progressively less real themselves. The humans who first left Earth, as seen in recordings, are portrayed by live-action human actors; in the portraits depicting the Axiom’s series of Captains over the centuries, we see a shift from actual humans to blobby computer-animated humans. Along similar lines, Wall•E and EVE are voiced by human actors making robot noises, but the Axiom’s overseer, the steering wheel AUTO, is voiced by the text-to-speech computer program MacInTalk. There is nothing real about him.

On the Earth, hands were the instruments of work and Love. It was through hand-to-hand touch that Wall•E related to his work, to the world around him, and to EVE (or at least, so he hoped). The Axiom, however – a ship named for an abstract, bodiless logical term – is a world without hand-to-hand contact. Thus, it is a world without fruitful labor or real relationships. On Earth, Wall•E worked during the day and rested at night. On the Axiom, the humans never work, and the robots never do anything but work. Josef Pieper might as well be describing the Axiom when he writes, “Cut off from the worship of the divine, leisure becomes laziness and work inhuman… The vacancy left by absence of worship is filled by mere killing of time and by boredom, which is directly related to our inability to enjoy leisure; for one can only be bored if the spiritual power to be leisurely has been lost.”16

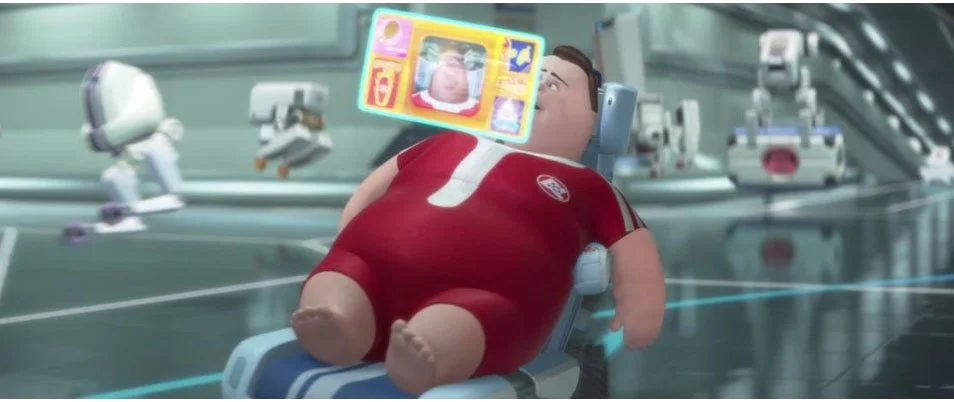

The Axiom is designed like a cruise ship, and the existence of its human passengers is designed to be an endless vacation, but this does not mean that they live lives of genuine restfulness. Wall•E’s life bears witness to the fact that rest is best when it complements a long, hard day of work. The humans on the Axiom, who have never worked a day in their lives, never truly rest either; they merely fritter their lives away in fruitless diversions. Wall•E was humanized through a screen, with his nightly viewings of Hello, Dolly!; the humans on the Axiom are dehumanized by the screens they spend their lives staring at. In contrast to Wall•E’s hands-on engagement with the world around him, even the passengers’ “leisure activities” are virtual. They do not play sports; they press buttons directing robots to play sports for them. Their lives are spent on hovering chairs; their feet never even touch the ground. The Captain does not know how to open an instruction manual with his hands – or even how to pronounce the word “Manual” (that is, “relating to or done with the hands”).

Even more perversely, in contrast to Wall•E’s longing to hold EVE’s hand – his yearning for hands-on connection with the Other – the humans’ interactions with each other are thoroughly virtualized. Two men sitting in adjacent hover chairs, mere feet apart from one another, have their conversation via videoconference instead of touching or even facing each other. There is no evidence of any families on the Axiom; the babies are taught, or indoctrinated, en masse by a robot nurse. (Frankly, the fact that there are babies on the Axiom at all constitutes a plot hole, because it is impossible to imagine these humans reproducing.) In fact, all of the humans on the Axiom are like infants, drinking “lunch in a cup” – they cannot endure solid food, and if they fall, they must be helped up.

There is no sense that the humans’ dutiful robot caretakers find any contentment in their work, the way Wall•E found contentment in his. Just as Wall•E’s work enabled him to enjoy his rest, his rest enabled him to enjoy his work. The robots of the Axiom, though, are without leisure, and thus live in what Josef Pieper called the world of “total work.”[17] AUTO and the robots under his command perform their functions under a blind, soulless compulsion, having forgotten or even outright rejected the greater purpose those functions are meant for.

Wall•E did his fruitful work with his hands and enjoyed his labor under the sun. AUTO and his minions, uncannily reflecting their infantile human makers, have no real, embodied relationship with the material they joylessly manipulate; they merely move things around with their minds. AUTO represents the logical endpoint of “total work”: with no hands, only an electric prod, he is utterly incapable of meaningful work or meaningful connection. All he can do is order, manage, control, and harm, to no greater end. When his minions order Wall•E to “Halt!”, they display an image of a hand on their screens. What else can they do? They have no real hands to speak of.

4

With the drawing of this Love and the voice of this Calling

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

– T.S. Eliot, “Little Gidding”

Wall•E began by framing its hero as the First Adam, alone on the Earth until the coming of Eve. The First Adam’s work was to tend a world created good; but when Wall•E reaches the Axiom, he takes on the role of Christ, the Second Adam, whose work is to redeem and restore a broken world. Wall•E is the agent of Re-Creation – of making the Creation new again, of making it good as it was originally meant to be. Wall•E restores the world of humanity by bringing to it what we might call the spirit of Sunday: the spirit of worship, of recognizing and celebrating the goodness of Creation, which is, as Pieper tells us, the only real foundation of fruitful work and true leisure. The spirit of Sunday consists in “man’s affirmation of the universe and his experiencing the world in an aspect other than its everyday one,”[18] and so it is closely tied to the experience of Love, which unveils the heavenly reality of things. “Riguarda qual son io” – “See me as I am.” Just as EVE’s arrival on Earth opened Wall•E’s eyes to look upon all things with Love, Wall•E’s arrival on the Axiom restores the vision of those living there, helping them to see the world with Love – to see it as it is, and thus to contemplate it anew with wonder and gratitude.

Wall•E restores the humans to relationship with each other by freeing them from the blindness of their dependence on screens, enabling them to see each other as they are – and once the humans can truly see each other, the natural next step is for them to truly touch each other. On the Cross, Christ restored the human family by bringing John and Mary together; befitting his role as the Second Adam, Wall•E inspires John and Mary to hold hands. Later, John and Mary will use those same hands to gather up the Axiom’s population of spiritually orphaned infants, bringing the human family together again in a relationship of love.

Wall•E – whose very name, like Adam’s, ties him to the Earth – also restores humanity to right relationship with the Creation. The humans on the Axiom, floating around in their hover chairs, need to get their feet back on the ground; aptly, then, they are saved by the plant that Wall•E and EVE bring to them in a shoe. Moreover, in a quite literal fashion, Wall•E brings the Earth to the Captain with his hands. When they meet, Wall•E shakes the Captain’s hand – a human gesture that no human seems to have performed for centuries – and leaves dirt on it. This dirt prompts the Captain’s joyous rediscovery of Earth: “The surface of the world, as distinct from the sky or sea”; “God called the dry land Earth, and the gathering together of the waters He called seas.”[19] Just as, in the Genesis account, Creation culminates in celebration, the Captain’s rediscovery of Creation climaxes with dancing: “A series of movements involving two partners, where speed and rhythm match harmoniously with music.”

Just as Wall•E was humanized by his viewing of Hello, Dolly!, the Captain is re-humanized by the screen displaying images of Earth, which fire him with longing to return home. As he looks on the Earth with new eyes, the round planet is projected over his face, visually linking him to the place where he belongs and the stuff of which he, as a descendant of Adam, is made. Wall•E, a type of Adam, inspires the Captain to also become like Adam – to take up the responsibility he has abdicated and be the one with dominion over the Creation. After receiving the plant in a shoe from EVE, the Captain stands on his own two feet; after receiving the Earth from Wall•E’s hands, the Captain overcomes AUTO with his hands. His final triumph comes when he switches the steering wheel from Auto (“working by itself with little or no direct human control”) to Manual (“worked by hand”).

Not all of the robots on the Axiom must be defeated, though; most of them must be redeemed and liberated. Wall•E descends into the Axiom’s repair ward and – mirroring the Second Adam’s Harrowing of Hell – frees the robots AUTO has imprisoned there. Crucially, the robots in the repair ward are not malfunctioning because they have ceased to work. Quite the opposite: they are malfunctioning because they have been consumed by their work, and now perform their functions excessively and indiscriminately. The defibrillator robot shocks everything, not just victims of cardiac arrest; the beautician robot applies makeup to everything, not just human faces. Wall•E frees the robots from this hellish world of “total work” by bringing them the spirit of Sunday. As Wall•E, EVE, and the other “rogue robots” charge the Axiom’s Holo-Detector, bringing the plant that will send the ship back to Earth, “Put On Your Sunday Clothes” from Hello, Dolly! becomes their anthem and their battle cry.

It is at the Holo-Detector that Love comes fully to fruition in Wall•E. The road of Love that began when Wall•E first saw EVE leads, as Love always must, to him giving up his life for her. The First Adam abdicated his vocation to put himself between his beloved and the tree that brought her death; the Second Adam redeemed the failure of the First and saved His beloved by submitting to death upon a tree; and Wall•E allows his body to be crushed to hold open the door for the new life of the plant, the new life towards which his beloved EVE has always called him.

At the end of the Paradiso, Dante finally turns his gaze away from Beatrice to God, and this development must occur in every relationship of Love. The Lover must always look beyond the Beloved to Love. And yet, paradoxically, it is only by this turning away that Love is ultimately made valid; it is only by submitting to the Crucifixion that Love can share in the Resurrection. Wall•E gives his life for EVE, and EVE's love restores Wall•E's life to him. Hello, Dolly! taught Wall•E that hands were meant to hold each other, and when EVE finally holds Wall•E's hand, their hands finally fulfill their function. Their Love, and thus their very existence, achieves its telos and is made complete.

Just as Wall•E is personally Re-Created by Love, the entire Cosmos is Re-Created by Love. Wall•E began by evoking Genesis, the beginning of the Christian story, and it ends by evoking Revelation, the end of the Christian story, with a new heavens and a new earth. When Wall•E and EVE present the plant to him, the Captain exclaims, “We can go back home! For the first time!” Love draws humans and robots back to the place where they began and opens their eyes to see it anew, the way it was meant to be seen – as a home, a place where humans and robots alike use their hands for fruitful work and real Love.

Epilogue

[I]n the performance of [the Eucharist] man, “who is born to work”, may truly be “transported” out of the weariness of daily labor into an unending holiday, carried away out of the straitness of the workaday world into the heart of the universe.

– Josef Pieper, “Leisure the Basis of Culture”

The Criterion Collection’s new edition of Wall•E includes some of the notes that Andrew Stanton wrote by hand during the development of the film. One scrawled note caught my eye and became the seed out of which this essay has grown: “Had this thought in church today.”

How perfect that Wall•E was born out of Stanton’s own divine worship on a Sunday morning. Though it was bankrolled by one of the largest corporations in the world, it is not a product of

“total work” but a gratuitous overflow of superabundant imagination and creativity. It is, in other words, a labor of Love.

In the Christian understanding of time, Sunday is both the first day of the week and the last. On Sunday, Christians perpetually commemorate the Resurrection of Christ on the first day of the week – the Resurrection which finished the old creation and began the new creation. Sunday is the quintessential day of rest, the day on which we are commanded to “Be still and know that I am God.”[20] Sunday is not a day of mere cessation from work, though; it is also the day that fulfills the work week and makes it fruitful by bringing it into the act of worship. In the Eucharist, we take God’s good, natural creation of grain and grape, transformed by human labor into bread and wine, offer it back to God, and receive it back from God as a supernatural gift – as the body and blood of His Son. On Sunday, we offer the work of our hands to God, and He takes our imperfect, inadequate work and makes it part of the work that He is doingThen we begin again, refreshed and empowered to do the good works He has created us to do. On Sunday, we “affirm the basic meaningfulness of the universe and a sense of oneness with it, of inclusion within it.”[21] On Sunday, we are at once gathered into God's rest and sent out to do God's work. This is the spirit of Sunday that Wall•E restores to his cosmos: in Love’s new creation, worship begets work, and work becomes a part of worship.

So put on your Sunday clothes. There’s lots of world out there.

________________________

1 Genesis 1:31

2 Genesis 3:17

3 Genesis 2:18, 20

4 Ecclesiastes 1:3

5 Ecclesiastes 2:24

6 C.S. Lewis, “Learning in Wartime”

7 Gerard Manley Hopkins, “God’s Grandeur”

8 Josef Pieper, Leisure the Basis of Culture

9 Exodus 20:8-11

10 Josef Pieper, Leisure the Basis of Culture

11 Charles Williams, The Figure of Beatrice

12 Charles Williams, The Figure of Beatrice

13 Charles Williams, The Figure of Beatrice

14 Dante Alighieri, Purgatorio

15 C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves

16 Josef Pieper, Leisure the Basis of Culture

17 Josef Pieper, Leisure the Basis of Culture

18 Josef Pieper, Leisure the Basis of Culture

19 Genesis 1:10

20 Psalm 46:10

21 Josef Pieper, Leisure the Basis of Culture

________________________

Timothy Lawrence is senior writer at FilmFisher, a Christian movie review site for educators and students that hosts over a hundred of his essays on faith and film. He shares short reflections on Christianity, popular culture, and the classics at The Usual Subjects. A graduate of Biola University's Torrey Honors College, he teaches great books through Emmaus Classical Academy in Southern California.