by Bill Thielker

Odd question, perhaps, but when I wonder about who I am, my mind meanders into what I do. Is what I do art? It rarely feels like some lofty pursuit, more often like a compulsion or at times the rants of near madness.

For most of my life, I have resisted calling myself an artist, preferring that title to be assigned by others. Yet, in spite of that reluctance, I know I am hardwired as an artist. My mother recalled how I wanted to draw from the time I could hold a crayon, spending hours on the kitchen floor doodling on scraps of paper. My father told of how he defended my artistic bent when it was criticized by my kindergarten teacher and, while doing so, realized I'd never follow in his aero-space engineer footsteps. Art has always been there, always a primary aspect of who I am though I often misunderstand what that means.

It was a decade or so ago that words, in a substantial way, joined the images in my head that wanted out, on paper. What came out some might call poetry. I, however, was not sure. Oddly, I am not a fan of poetry or reading in general for that matter (thank you dyslexia for that gift) so could not hold my word assemblages up to some familiar yardstick to estimate their size. But when a friend who is a retired English professor, former academic dean and interim president of a top-tier college, referred to my word scribbles as poetry and me as a poet, I accepted it.

While I appreciate others calling me an artist or poet, I still feel a slight discomfort when they do. I suspect that discomfort arises from not being altogether certain that what I do has any tangible value or meaning, mingled with ongoing misunderstanding of who I am. Then, quite unexpectedly, into this melange enter the words of Shakespeare spoken by Cambridge professor Malcolm Guite:

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.1

Those words stuck to me, in particular the last phrase "and gives to airy nothing a local habitation and a name.” Reading Shakespeare for me is a remedy for insomnia, yet he so succinctly described a quality and function of art which I had never heard expressed before. Malcolm did not just speak those words, he also provided them on a handout. Words Shakespeare intended to be spoken had been given a habitation on the piece of paper I was holding, a place where they could dwell, long after the sound of the speaking faded from my hearing. I folded the paper and stuffed it in my pocket. Even though out my sight, the words resounded in my memory, in a voice imbued with the potential to dissipate fog, bring clarity.

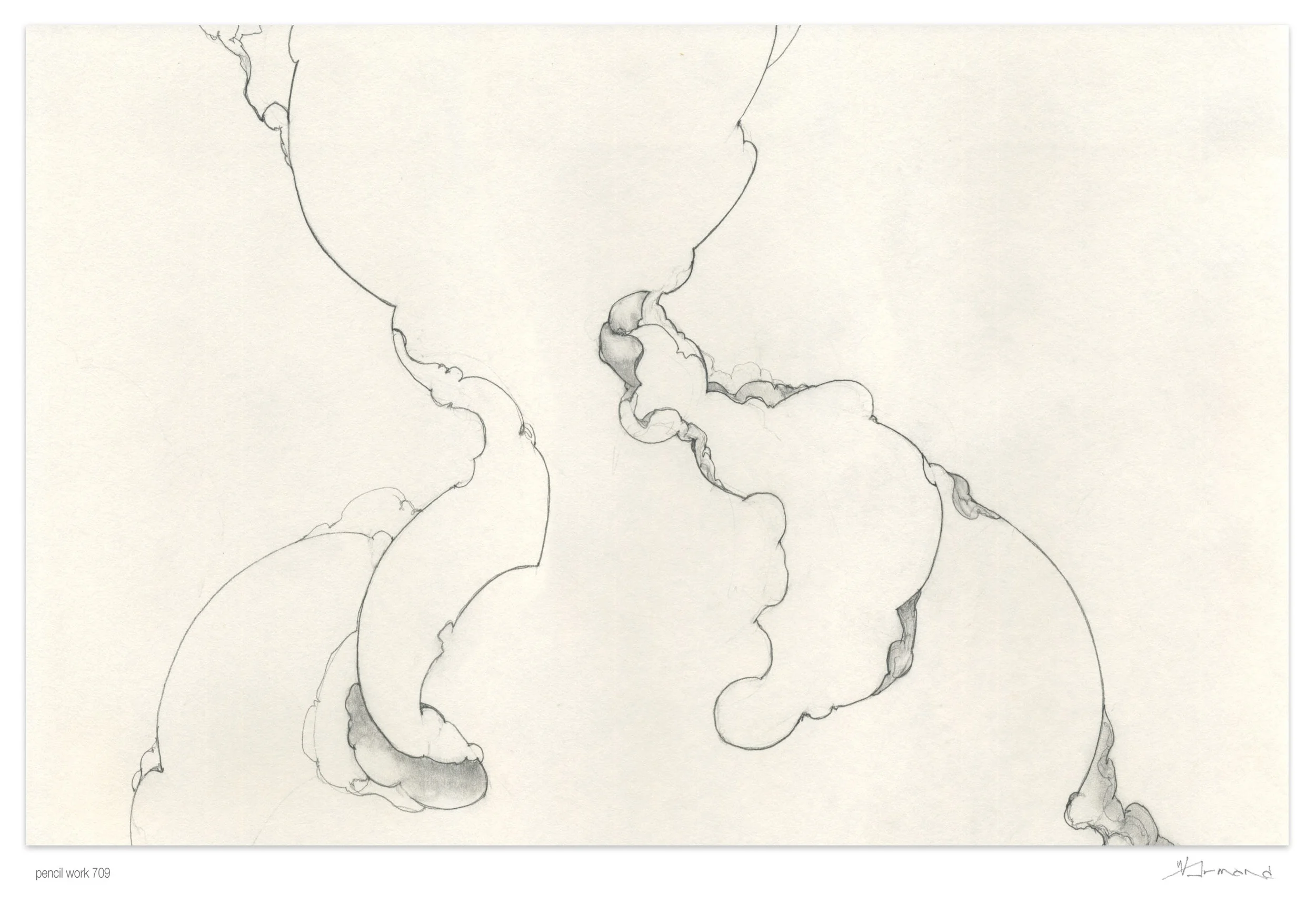

In the weeks following the reverend doctor's talk, I have looked again and again at those words. With each reading, a bit more misunderstanding has dissipated. So much of what I do has seemed like formless imagination, like airy nothing. Yet, my photographs freeze a fragment of time and hold it still so we can linger in the briefest of moments. The lines of my abstract pencil sketches give a frame onto which imagination can hang. The assembled words of my poetry briefly point in directions less traveled.

When things unknown are given shape and airy nothing a place to live and a name by which to be called, they lose their wispy nothingness and take on substance, a substance which can be held, grasped.

They all dwell somewhere. First in a dormant state on paper, then come to life again in imagination and memory, mingled with the life-hues of those who read the words or gaze on the images.

Art is what I do and also who I am. It is what I do because it is who I am. I am discovering that I am a giver of shape to imagined formlessness and a provider of name and address for airy nothing.

1 A Midsummer Night’s Dream Act 5, Scene 1

Pencil sketch: by the author.